This was originally published in Rolling Stone India, November 2009. Dusted and put up here because I plan to do a mega-reread of the series in the next few days.

Writer/Artist: Tohru Fujisawa

Publisher: Tokyopop

Rating: Four and a half stars

Meet Eikichi Onizuka, a bottom-rung university graduate (barely), whose primary interests are peering up girls’ skirts at local malls and getting into trouble – not mutually exclusive activities, those two. But fate has different plans in store for virginity-challenged young Eikichi – circumstance makes him leave his delinquence behind him and opt for a new career, that of an educator. Eikichi Onizuka, 22 years old, sets out to become Great Teacher Onizuka, the greatest sensei in Japan. His mission: to make school fun again. His secondary mission – getting to fourth base with someone. Anyone.

That is the premise behind this beloved shonen manga series, that traces Onizuka’s explosive – and often ludicrous – adventures in teaching. At first glance, it seems humanly impossible for a man of his calibre to really do much with his career choice. He cheated his way through his own academic career, seemingly has an IQ of 50, and the only legitimate qualification on his misspelled resume is that he has secured a second dan black belt in karate. He is perverted, being more than a little obsessed with young girls and their underwear. And he lets his fists do the talking most of the time. The first arc of the series establishes how Onizuka, beating all these odds, manages to get through a teacher training course at a public school and becomes a temporary teacher in the Holy Forest Academy, a prestigious private institute. He is put in charge of Class 3-4, whose students have terrorized the previous three home-room teachers into ending their careers – one committed suicide, another developed an eating disorder. It would take a very foolhardy, or a very determined educator to take up the responsibility of cleaning the school’s Augean stables.

But determination is what Onizuka has in spades. “You are a cockroach”, one of his students shrieks at him with disgust, right after the would-be teacher pops up where he wasn’t really supposed to. This analogy echoes throughout the series. Like a cockroach, Onizuka wiggles himself into his students’ lives even as they hurl expletives at him and threaten (and often perpetrate) violence against his self. Just as a cockroach skitters away from all attempts to stomp it out, our hero manages to best all the traps his devilish students cook up – from publishing morphed porno pictures of Onizuka to having him framed for embezzling money from student funds. And slowly, one by one, our hero wins them over using a combination of his perversely inappropriate world-view and his incredible physical prowess.

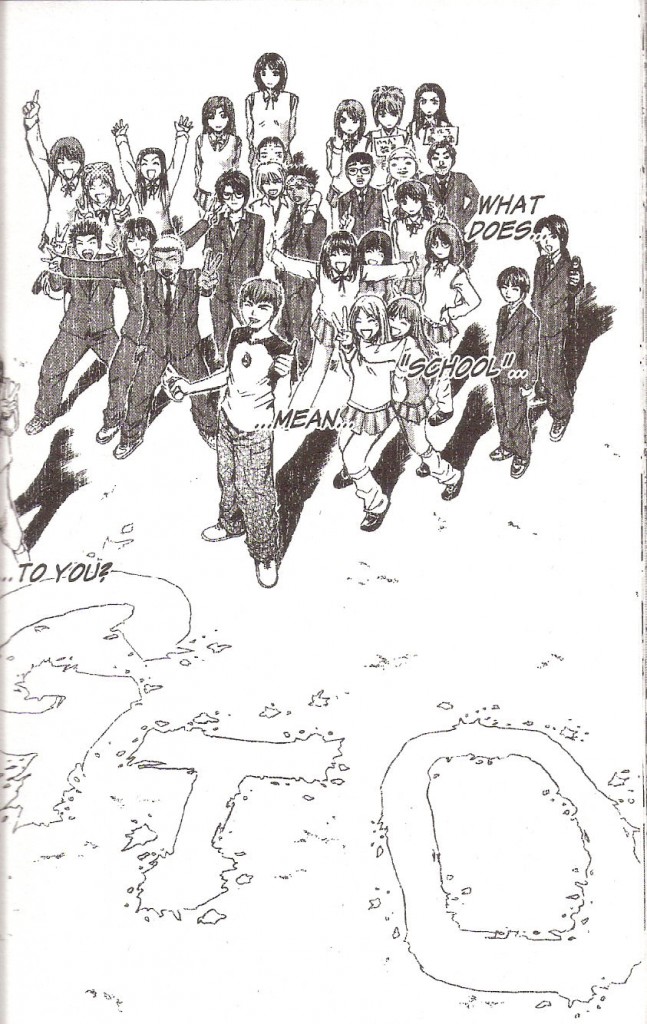

All long-running series by single creators run into similar teething issues – an initial rush of heady ideas that slowly slides into a predictable graph of highs and lows, where the creator struggles not only to find the voice, but to etch out a character’s life-story in a way that builds on its premise, instead of stagnating into repetitive cliche. Maintaining the momentum of a series, without over-stretching a story-line is a tough call. It would have been very easy for writer/artist Tohru Fujisawa to stumble. The second arc, that of the students being set straight by the teacher, resolutely avoids falling into the trap. Sure, it is long, but there are two aspects in which Fujisawa scores top of the manga-ka class (if you will pardon the school-based metaphor) – the delineation of the individual characters that make up the Onizukaverse. Every student in the class has a unique personality, a standalone voice which makes the reader identify with them. Partly because they are there in every classroom in any school in the world – the quiet, shy video-game-playing geek who is bullied at every turn; the computer whiz who knows more than he lets on; the headstrong yet confused loud-mouth who takes offence at minor quips; a girl whose parents are influential bureaucrats, a fact that she uses to her advantage; another with a dark secret involving a previous teacher. Sure, they are all genre archetypes, but it is Fujisawa’s genius that breathes new, fresh life into them.

The second thing that elevates the series to greatness is the sheer unpredictability of the central character. Eikichi Onizuka is a man of hidden surprises, whose heart of gold is matched only by his complete irreverence and lack of respect for authority. Early on in his career, Onizuka figures out that he really loves teaching, and he takes it on himself to be the kind of teacher that his generation did not have. At the crux of every decision Onizuka makes, however frivolous and played-for-laughs it seems to be, there is an important life-lesson that he imparts to his students. But Onizuka being the way he is, any attempt to take him seriously usually backfires, with hilarious results.

In addition to changing the way his students feel towards school, Onizuka also takes on the strict authoritarians that make up the faculty of Holy Forest Academy. His primary whipping-dog being the perennially grumpy Vice-Principal Uchiyamada – a running gag involves the Vice-Principal’s Toyota Cresta. The third arc of the series, in particular, involves a final stand against a new Principal who ousts the support of Chairman Sakurai, whose tacit approval had made a large part of Onizuka’s brushes with authority seem minor in the past.

Great Teacher Onizuka made me laugh, it had me gasping with incredulity, it made me come up with excuses to avoid work just so I could tear through the twenty-five volumes as soon as I could. It is not without its faults – a great deal of fan-service persists throughout the story, and let’s face it – if you have seen To Sir With Love and Munnabhai MBBS, you realize that the premise of GTO is hardly original. But even with all its over-the-top antics, it’s not just a fine comedy series, but also a drama that’s an indictment of the pettiness that afflicts today’s education system. It’s a scathing denouncement of self-serving, vainglorious modern-day teachers for whom teaching is nothing more than a way to make money, rather than the life-altering position it is meant to be. Hey, it made me want to go back to school, and that’s quite something!